-

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà...

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà... -

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu -

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

- Publisher:Mountaineers Books (April 18, 2023)

- Language:English

- Paperback:176 pages

- ISBN-10:1680516132

- ISBN-13:978-1680516135

- Item Weight:8.8 ounces

- Dimensions:5.75 x 0.75 x 7.75 inches

- Best Sellers Rank:#91,464 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #15 in Biology of Dogs & Wolfs #162 in Environmentalism #743 in U.S. State & Local History

- Customer Reviews:4.8 out of 5 stars 6Reviews

Mô tả sản phẩm

From the Publisher

From Chapter 1: Wolf 258

In early November 2010, two wolves coursed the open slopes above Copper Creek, a tributary of the upper Charley River. Snow from a recent squall persisted in the lee of granite tors, and ice rimmed the shadowed rivulets. Scattered caribou grazed on a nearby ridge, while a nervous band of Dall sheep climbed sheer cliffs. The wolves, alert, were hunting.

The day was sunny and unseasonably warm, at 45°F, and the wind light, ideal conditions for flying. When the wolves heard the helicopter approaching fast and low, they broke into a run. As it grew louder and closer, the wolves parted ways. One, a black female known to biologists as Wolf 227, wore a radio collar. The helicopter was locked onto her signal, betraying her and her companion.

Biologist John Burch signaled to the pilot that he wanted to dart Wolf 227’s companion. As the helicopter closed in, the companion wolf veered wildly to shake the pursuit. But the pilot was an expert at chasing wolves. On this tundra hillside, escape was improbable. Sitting in the open door, and blasted by rotor wash, Burch fired his tranquilizer gun and struck the wolf’s flank with 500 milligrams of Telazol, a safe, fast-acting veterinary anesthetic that has an analgesic effect. The small helicopter flared and banked away. Within a few minutes, the wolf went down.

Burch, tall and soft-spoken, had been tracking Yukon-Charley wolves since 1996, when he took over the fieldwork from biologist Nick Demma. A Minnesotan, Burch earned a bachelor’s degree in wildlife biology from the University of Minnesota and a master’s degree in wildlife biology from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. While still an undergraduate, he began working with L. David Mech in Minnesota on a variety of wolf research projects. Before coming to Alaska in 1985 to conduct wolf research in Denali National Park and Preserve for Mech, Burch worked tracking and trapping wolves for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, primarily in Minne- sota and Wisconsin. Burch had more than two decades’ experience working with wolves when he joined the Yukon-Charley project. When it came to catching and handling wolves, he had few peers. Over his career, he darted and collared between four hundred and five hundred wolves.

Colleagues regarded Burch highly. “John is one of the most competent field biologists I have ever worked with,” said Adams. “At Yukon-Charley, John became recognized as the guy you wanted along if you were working in remote locations. He’s one of those adept field folks who can adapt to whatever he is facing, fix anything, work for long stretches under trying environmental conditions, and keep a good attitude throughout it all.”

After the helicopter landed, Burch hurried to the sedated wolf. A quick appraisal showed this young wolf was tolerating the drug. Burch had about an hour before it would begin to revive.

The sedated wolf weighed 103 pounds and was about two years old. He was well furred and appeared to be in excellent health, with perfect teeth. Based on their location and previous sightings, he guessed that the young male, now designated Wolf 258, was a disperser from the Seventymile River Pack.

Wolf researchers typically apply sequential numbers to their collared subjects, such as Wolf 227 and Wolf 258. Naming conventions for other wolf projects vary slightly. In Voyageurs National Park, for example, each collared animal is identified with VO, such as Wolf VO77, for Voyageurs. In Denali National Park, wolves get a four-digit code with letters for their color and sex—Wolf 1804GM (GM for gray male) or Wolf 1841GF (GF for gray female). The first two digits represent the year the wolf was collared, and the last two indicate where it falls in the order of wolves collared that year. Common names, such as Blackie or George, are anathema to biolo- gists, who avoid anything anthropomorphic.

After fitting the male wolf with a GPS collar, Burch, assisted by the pilot, collected vital signs: temperature, pulse, respiration rate, and blood oxygen level. They then took cheek swabs and hair samples and drew some blood, both to check for disease and to perform genetic analysis. (Analysis later confirmed that the two wolves were unrelated.) They weighed the wolf and examined his teeth for clues as to its age and condition. Burch finished just as the wolf began to revive. The wolf would be left to recover quietly on his own, although these days, biologists stay with a sedated wolf until it has recovered fully.

The young gray-and-white male was traveling with a collared female Burch knew well. He had first captured Wolf 227, then the breeding female of the Edwards Creek Pack, three years earlier. For the past two years she’d been traveling alone as the last surviving member of her pack, seldom ven- turing out of her core range on Washington Creek. This capture site on the upper Charley River was out of her normal territory; she had ventured into the range of the Seventymile River Pack, whose territory extended east from the upper Charley River into the Seventymile River drainage. Early in the summer, Burch had spotted her traveling with another wolf and thought she’d paired up. The young male wolf he’d just collared confirmed his sus- picions, and he was keen to find out if the sedated male was just a running partner or a mate to Wolf 227. Although two wolves are often called a pack, the key determinant is whether they produce pups.

Dominant wolves breed, fight, and are able to pull down a caribou alone. Researchers typically capture and radio-collar one to three individuals, pri- marily the breeders, in each wolf pack in a study area. Other pack members hunt and defend territory, but they don’t breed or make decisions for the group. Because the breeding pair is least likely to leave a pack, researchers routinely capture and collar them.

Burch caught Wolf 227 later that afternoon and replaced her old, failing collar. Despite running solo for two years, the six-year-old female had killed enough prey to stay in superb condition. She’d also managed to hold on to her core territory—or at least avoid lethal contact with trespassing packs. The collars would reveal mating and denning behavior. How the new pairing would affect territorial dynamics was but one of many questions Burch hoped the tracking collars would answer.

At the time, biologists used two types of radio collars to track wolves. A conventional radio collar, in use for decades, transmits a pulsing signal that can be tracked from an aircraft equipped with a receiver and antennae. A GPS collar, on the other hand, transmits coordinates through a satellite to a computer, allowing biologists to more accurately monitor a wolf’s travels, life, and death. Like a radio collar, a satellite collar can be tracked from aircraft, but the big difference is that location data is collected automatically. A GPS collar reveals a wolf’s day-to-day movements across territory in search of food; thus a wolf remaining close to a particular site for a day or two may indicate it has killed a prey animal and is feeding. Biologists began putting GPS collars on wolves in the Yukon-Charley National Preserve in 2003. Burch was confident that the two new collars would transmit valuable information about the fate of the Edwards Creek Pack, one of a dozen he monitored then. Before flying off, Burch paused for a few moments of silent contemplation. He never seemed to lose his appreciation for wolves and the surrounding wilderness.

- Mua astaxanthin uống có tốt không? Mua ở đâu? 29/10/2018

- Saffron (nhụy hoa nghệ tây) uống như thế nào cho hợp lý? 29/09/2018

- Saffron (nghệ tây) làm đẹp như thế nào? 28/09/2018

- Giải đáp những thắc mắc về viên uống sinh lý Fuji Sumo 14/09/2018

- Công dụng tuyệt vời từ tinh chất tỏi với sức khỏe 12/09/2018

- Mua collagen 82X chính hãng ở đâu? 26/07/2018

- NueGlow mua ở đâu giá chính hãng bao nhiêu? 04/07/2018

- Fucoidan Chính hãng Nhật Bản giá bao nhiêu? 18/05/2018

- Top 5 loại thuốc trị sẹo tốt nhất, hiệu quả với cả sẹo lâu năm 20/03/2018

- Footer chi tiết bài viết 09/03/2018

- Mã vạch không thể phân biệt hàng chính hãng hay hàng giả 10/05/2023

- Thuốc trắng da Ivory Caps chính hãng giá bao nhiêu? Mua ở đâu? 08/12/2022

- Nên thoa kem trắng da body vào lúc nào để đạt hiệu quả cao? 07/12/2022

- Tiêm trắng da toàn thân giá bao nhiêu? Có an toàn không? 06/12/2022

- Top 3 kem dưỡng trắng da được ưa chuộng nhất hiện nay 05/12/2022

- Uống vitamin C có trắng da không? Nên uống như thế nào? 03/12/2022

- [email protected]

- Hotline: 0909977247

- Hotline: 0908897041

- 8h - 17h Từ Thứ 2 - Thứ 7

Đăng ký nhận thông tin qua email để nhận được hàng triệu ưu đãi từ Muathuoctot.com

Tạp chí sức khỏe làm đẹp, Kem chống nắng nào tốt nhất hiện nay Thuoc giam can an toan hiện nay, thuoc collagen, thuoc Dong trung ha thao , thuoc giam can LIC, thuoc shark cartilage thuoc collagen youtheory dau ca omega 3 tot nhat, dong trung ha thao aloha cua my, kem tri seo hieu qua, C ollagen shiseido enriched, và collagen shiseido dạng viên , Collagen de happy ngăn chặn quá trình lão hóa, mua hang tren thuoc virility pills vp-rx tri roi loan cuong duong, vitamin e 400, dieu tri bang thuoc fucoidan, kem chống nhăn vùng mắt, dịch vụ giao hang nhanh nội thành, crest 3d white, fine pure collagen, nên mua collagen shiseido ở đâu, làm sáng mắt, dịch vụ cho thue kho lẻ tại tphcm, thực phẩm tăng cường sinh lý nam, thuoc prenatal bổ sung dinh dưỡng, kem đánh răng crest 3d white, hỗ trợ điều trị tim mạch, thuốc trắng da hiệu quả giúp phục hồi da. thuốc mọc tóc biotin

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN

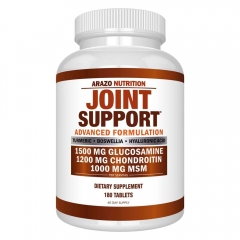

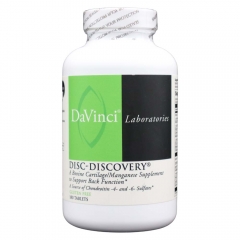

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp

Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ

Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp

Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc

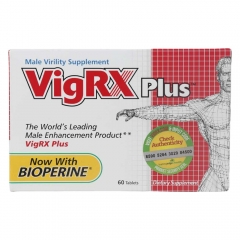

Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em

Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng

Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất

Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu

Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực

Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng

Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa

Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng

Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.

Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.