-

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà...

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà... -

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu -

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

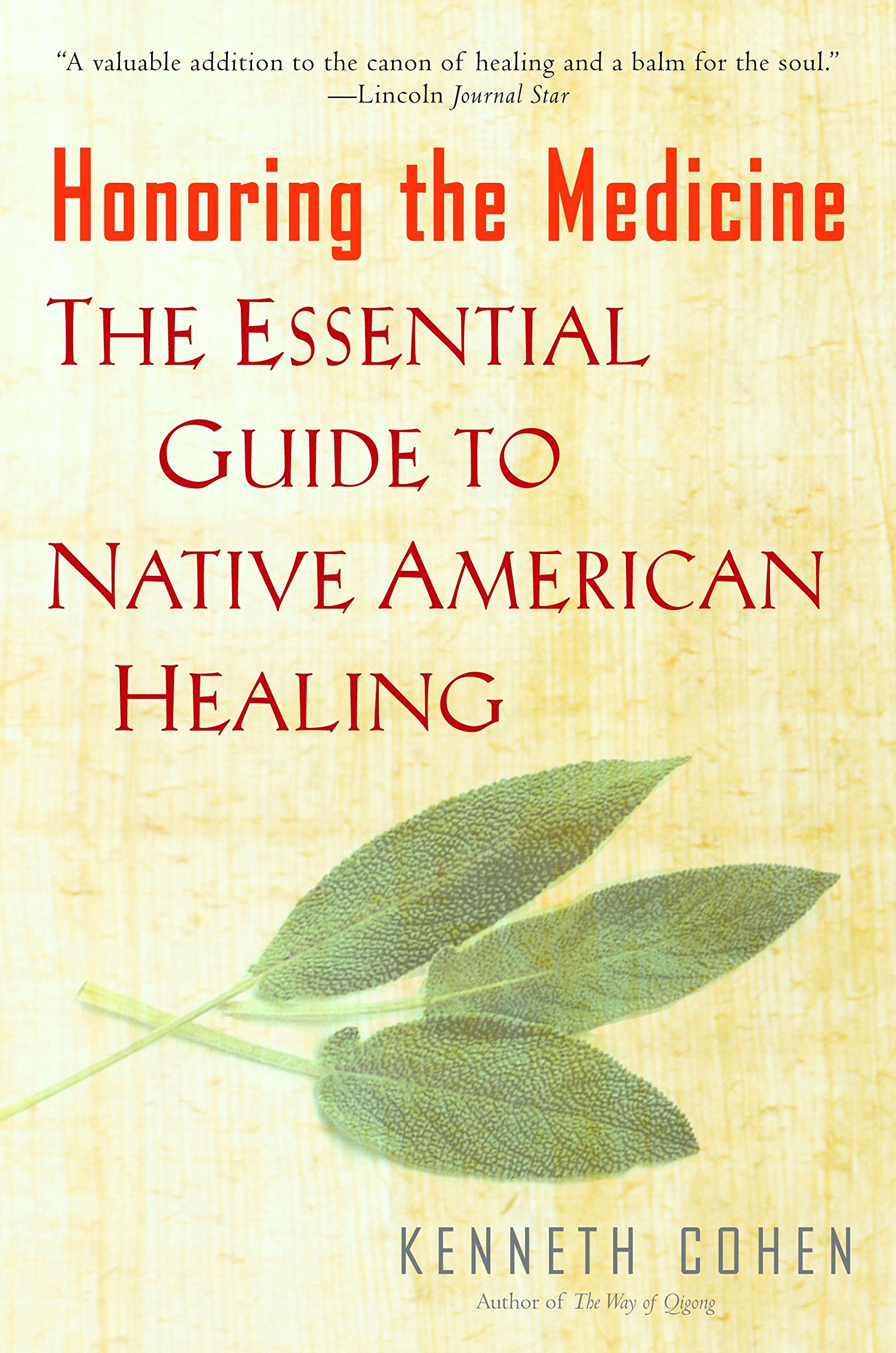

Honoring the Medicine: The Essential Guide to Native American Healing

-

- Mã sản phẩm: 0345435133

- (177 nhận xét)

- Publisher:Ballantine Books; Reprint edition (June 27, 2006)

- Language:English

- Paperback:464 pages

- ISBN-10:0345435133

- ISBN-13:978-0345435132

- Item Weight:1.14 pounds

- Dimensions:6.09 x 1 x 9.21 inches

- Best Sellers Rank:#633,766 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #268 in Native American Religion #1,963 in Healing #3,626 in Mental & Spiritual Healing

- Customer Reviews:4.7 out of 5 stars 180Reviews

Mô tả sản phẩm

Product Description

For thousands of years, Native medicine was the only medicine on the North American continent. It is America’s original holistic medicine, a powerful means of healing the body, balancing the emotions, and renewing the spirit. Medicine men and women prescribe prayers, dances, songs, herbal mixtures, counseling, and many other remedies that help not only the individual but the family and the community as well. The goal of healing is both wellness and wisdom.

Written by a master of alternative healing practices, Honoring the Medicine gathers together an unparalleled abundance of information about every aspect of Native American medicine and a healing philosophy that connects each of us with the whole web of life—people, plants, animals, the earth. Inside you will discover

• The power of the Four Winds—the psychological and spiritual qualities that contribute to harmony and health

• Native American Values—including wisdom from the Wolf and the inportance of commitment and cooperation

• The Vision Quest—searching for the Great Spirit’s guidance and life’s true purpose

• Moontime rituals—traditional practices that may be observed by women during menstruation

• Massage techniques, energy therapies, and the need for touch

• The benefits of ancient purification ceremonies, such as the Sweat Lodge

• Tips on finding and gathering healing plants—the wonders of herbs

• The purpose of smudging, fasting, and chanting—and how science confirms their effectiveness

Complete with true stories of miraculous healing, this unique book will benefit everyone who is committed to improving his or her quality of life. “If you have the courage to look within and without,” Kenneth Cohen tells us, “you may find that you also have an indigenous soul.”

Review

“This landmark book is a stunning tour de force. Ken Cohen has crafted a comprehensive yet accessible compilation of the theory and practice of Native American medicine. Honoring the Medicine is the rarest of books.”

—JEFF LEVIN, PH.D., M.P.H.

Author of God, Faith, and Health

“Ken Cohen writes from a place of beauty, truth, and integrity. He inspires us to reconnect with traditional ways for healing the earth and ourselves. [Honoring the Medicine] is a brilliant work.”

—SANDRA INGERMAN

Author of Soul Retrieval

“Anyone wanting insight into the world of Native American healing will be wise to read this remarkable, penetrating work. This is a valuable addition to the canon of healing.”

—LARRY DOSSEY, M.D.

Author of Healing Beyond the Body

About the Author

Kenneth “Bear Hawk” Cohen,is an internationally renowned health educator dedicated to the community of All Relations. He has trained with elder healers from all over the world and followed the path of indigenous wisdom for more than thirty years. Author of The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing and more than two hundred journal articles on spirituality and complementary medicine, he lives with his family in the Colorado Rockies.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

NATIVE AMERICAN

OR AMERICAN INDIAN

Can You Be Politically Correct?

Although Shakespeare said, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” you are less likely to want to see, smell, or buy a rose if a florist offers to show you “a blood-colored outgrowth of a thorny shrub.” Names do make a difference. Minorities and oppressed people are especially sensitive to the terminology used to describe them or their culture. The same words may mean different things to Native

Americans or to white people, or they may be insulting in one language and either meaningless or used inappropriately in another. For example, no Native American woman wants to be referred to as a squaw, an Algonquian-based insult. A Native American physician does not expect to be called “chief.” Some tribes are designated by strange foreign terms like Gros Ventre (“Big Bellies”), Nez Perce (“Pierced Noses”), or Apache (a Zuni Indian word meaning “enemy”). Native cultural and religious terms are sometimes appropriated by Western businesses for their commercial value. Would you feel comfortable riding in a Jeep Jew or drinking Communion Beer?

I have also seen people go to the other extreme: they try so hard to make every word polite and politically correct that they become tongue-tied, like a centipede that is asked, “How do you move all those legs?” I once met a young white man who had learned Indian sign language from a book and planned to use it when he visited an Indian reservation. He believed that this would demonstrate his respect for tradition. I was sorry to disappoint him: “When Indian people don’t speak one another’s languages, they communicate in English. People are likely to think that you are ‘signing’ because you’re deaf.” I don’t wish to scare you from talking with or about people who are unfamiliar. If you speak with a Native American and are unsure about appropriate terminology, simply ask. Your question communicates respect.

AMERICAN INDIAN OR NATIVE AMERICAN?

There are problems inherent in any of the terms commonly used by both indigenous and nonindigenous people to designate the original inhabitants of Turtle Island (an ancient indigenous name for North America). In precolonial times, a general term for aboriginal Americans was unnecessary and did not always exist.

Today, as in the past, Native Americans identify themselves by family, community (or band), clan, and nation. A Native American clan is a group of people who recognize kinship because of a special relationship to or descent from a common ancestor or ancestral group. Clans may be named after a deed, characteristic, or totem (Algonquian for “helping spirit”) of the ancestor—for example, the Bad War Deeds

Clan, Long Hair Clan, Bear Clan, Wolf Clan, Caribou Clan, Wind Clan, Salt Clan, or Yucca Fruit Clan. The words nation and tribe are often used interchangeably, though the term nation is generally more appropriate. The word tribe means a social group of numerous families and generations that share a common history, language, and culture. A nation is a tribe that is also a politically distinct entity and has the right to self-determination.

How would an ancient indigenous American identify himself or herself? ACherokee woman living five hundred years ago would not call herself an American Indian. She might say, “I am Saloli [a common personal name, meaning “Squirrel”], an Ani Wahya [Wolf Clan member] Ani Yunwiya [Cherokee], from Kituwah [an ancient town site, near present Bryson City, North Carolina].” Saloli’s people call

themselves Ani Yunwiya, the Principal People, in their own language. In other Indian languages, a tribal designation might refer to the tribe’s lodges (Haudenosaunee, “People of the Longhouse”), a sacred animal (the Absarokee, “Children of the Long-Beaked Bird,” the Raven or Crow), or their lands (Tsimshian, “Those inside the Skeena River” in British Columbia).

Christopher Columbus, a lost sailor discovered by the Taino tribe of the Antilles in 1492, called the indigenous people he encountered los Indios, “Indians,” because these gentle and generous people were una gente en Dios, “a people in God.” Some scholars believe that the term Indian may reflect Columbus’s belief that he had landed in India, an apt indication of his lack of orientation. The English, French,

and Italian colonial invaders who followed him lumped all of Turtle Island’s original inhabitants together as “savages” or other similar terms derived from the Latin silvaticus, meaning “a person of the woods” (silva). By the seventeenth century, Indians became the common designation, although the French continued to use sauvage through the nineteenth century. In 1643, Englishman Roger Williams sum-marized the common range of nomenclature in A Key into the Language of America; Or, An Help to the Language of the Natives in That Part of America Called New-England: “Natives, Savages, Indians, Wild-men (so the Dutch call them Wilden), Abergeny men, Pagans, Barbarians, Heathen”—terms that reflected and reinforced the Europeans’ belief in the moral, theological, cultural, and biological inferiority of America’s original inhabitants.

The tone soon shifted. The new Euro-Americans began to refer to the Native Americans as wild animals rather than wild men. In Indians of California: The Changing Image, James J. Rawls, Ph.D., history instructor from Diablo Valley College in Pleasant Hill, California, writes that “whites often compared California Indians to creatures that they regarded as especially repulsive”: snakes, toads, baboons,

and hogs. Supported by an anthropocentric theology that placed man at the center of creation, Christians could exterminate “pests and vermin” without com-punction. Similarly, modern soldiers find it easier to wage war against labels—“Nips,” “Gooks”—than against human beings with souls and families. Generalizations and stereotypes also serve political ends, as they allow legislators to promote laws that manipulate the fate of widely divergent people with unique needs and lifestyles while emphasizing American unity and nationalism.

Today, it is virtually impossible to find a universally satisfactory or politically correct term for the original people of this continent. When one of my Cherokee elders was referred to as an “American Indian,” he exclaimed, “I ain’t no damn Indian! I’m a Native American.” Yet most of America’s original inhabitants do call themselves “Indians” among themselves. A Cree friend calls himself “Indian” but re-minds

me that in Canada, the preferred generalization is “First Nations.” “Yet,” he tells me, “I prefer Native American in literature. The term feels more elegant.” So he becomes an “Indian” in everyday life and a Native American in books. A consistent designation is important for clarity. I do not wish to perpetuate confusion by referring to the “aboriginal, indigenous, Indian, Native Americans of the First Nations.” Frankly, I like to call the indigenous people “the People,” a term consistent with the words used for original Native nations in their own languages. In the Cree language, indigenous North Americans are collectively referred to as iyiniwak, “Peoples.” The names of many individual tribes, when translated, also simply mean “the People.” An Innu (“the People” of Labrador, Baffin Island, and Québec) elder and friend, N’tsukw, has a definition that is a real gem: “We call ourselves the People because we know that we are only just people, two-leggeds, not better or higher than any other form of life or any other aspect of Creation.” In this book, I have opted for elegance and generally referred to the People as Native American. I will, however, sometimes use the terms Indian, First Nations (when referring specifically to Canadian Indians), or indigenous (when my discussion is relevant to indigenous people of other lands).

WHO IS NATIVE AMERICAN?

What makes a person a Native American? This is an important and controversial topic. Is a person a Native American because of his or her ancestry, culture, or political status, or because of self-identification, which may or may not be verifiable? Who is entitled to live on tribal lands or share tribal revenue? Whose voice must be heard when consensus decisions are made either within Indian nations or between

Indian nations and foreign governments? Who has the right to carry a Native American passport?

Criteria that establish Indian identity may include membership in or adoption by a recognized Indian family, a specific percentage of Indian “blood” (blood quantum, in legal terms), or residence on tribal lands. Among some tribes, to claim tribal membership, you need only trace your genealogy to a Native American ancestor. (By this definition, former American President Bill Clinton is Cherokee.)

The United States government has frequently issued statutes that attempt to define Native ethnicity in order to clarify the rights of its “domestic dependent nations.” The results have been uniformly disastrous. For example, during the early nineteenth century, many Native people did not register on U.S. government– sponsored tribal rolls. They did not recognize United States jurisdiction or care about the government’s attempts to quantify them. Today, their descendants are clearly Native American, though not in the eyes of the U.S. government. Entire tribes, such as the forty-thousand-member Lumbee of North Carolina and the Duwamish of Washington (tribe of the famous Chief Seattle), remain unrecognized and are defined by the United States as nonexistent, often because of ignorance of

a tribe’s history and continuity; a lack of distinct, treaty-guaranteed lands; and greed for title over contested tribal homelands and their resources.

The Native American identity issue was highlighted in 1990 with the passage of the United States Indian Arts and Crafts Act. The act made it illegal for non-Indians to sell goods that are labeled “Indian-made.” The law was designed to protect both consumers and Native Americans and has a clear application when you turn over an “Indian-made” pottery bowl and discover that it was “made in Japan.” The law, however, also allows the U.S. government to prosecute Native Americans who do not meet United States definitions of identity. A descendant of a nonenrolled Native American or a member of a Native American community who does not have the requisite blood quantum can no longer legally sell “Indian-made” jewelry at a pow-wow.

The real issue here is not what determines Indian identity but who determines it. The question of Indian identity should not be in the hands of United States courts in the first place but rather decided by Native American nations and communities. Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) scholar Taiaiake Alfred brings wisdom and clarity to the issue:

Respecting the right of [indigenous] communities to determine membership for themselves would promote reconstruction of indigenous nations as groups of related people, descended from historic tribal communities, who meet commonly defined cultural and racial characteristics for inclusion.

TERMS FOR NATIVE NATIONS

Many of the English names for Native American nations are based on derogatory terms used by the enemies of those nations. For example, the names Iroquois and Sioux are derived from words that mean “enemy.” The word Mohawk, one of the six nations that comprise the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Tuscarora), is based on an Algonquian word that means “cannibal monster.” They call themselves Kanien’kehaka, People of the Flint. Some tribal designations are based on insulting remarks about a tribe’s way of life, such as Eskimo, derived from a phrase meaning “eaters of raw meat,” or Naskapi, meaning “uncivilized.” In this book, I use tribal names that are widely recognized by both Native and non-Native scholars as respectful designations (see the accom-panying table). I hope that other people who refer to Native American nations will continue this custom and adopt designations preferred by the tribes. In order not to confuse the reader, however, I will sometimes use less exact terminology when referring to peoples who have distinct words for each of their many bands or who use common tribal names among outsiders but different, more personal terms among themselves. (The Apache, Arapaho, and Comanche, for example, call themselves the Inde, Inunaina, and Nerm, respectively.)

- Mua astaxanthin uống có tốt không? Mua ở đâu? 29/10/2018

- Saffron (nhụy hoa nghệ tây) uống như thế nào cho hợp lý? 29/09/2018

- Saffron (nghệ tây) làm đẹp như thế nào? 28/09/2018

- Giải đáp những thắc mắc về viên uống sinh lý Fuji Sumo 14/09/2018

- Công dụng tuyệt vời từ tinh chất tỏi với sức khỏe 12/09/2018

- Mua collagen 82X chính hãng ở đâu? 26/07/2018

- NueGlow mua ở đâu giá chính hãng bao nhiêu? 04/07/2018

- Fucoidan Chính hãng Nhật Bản giá bao nhiêu? 18/05/2018

- Top 5 loại thuốc trị sẹo tốt nhất, hiệu quả với cả sẹo lâu năm 20/03/2018

- Footer chi tiết bài viết 09/03/2018

- Mã vạch không thể phân biệt hàng chính hãng hay hàng giả 10/05/2023

- Thuốc trắng da Ivory Caps chính hãng giá bao nhiêu? Mua ở đâu? 08/12/2022

- Nên thoa kem trắng da body vào lúc nào để đạt hiệu quả cao? 07/12/2022

- Tiêm trắng da toàn thân giá bao nhiêu? Có an toàn không? 06/12/2022

- Top 3 kem dưỡng trắng da được ưa chuộng nhất hiện nay 05/12/2022

- Uống vitamin C có trắng da không? Nên uống như thế nào? 03/12/2022

- [email protected]

- Hotline: 0909977247

- Hotline: 0908897041

- 8h - 17h Từ Thứ 2 - Thứ 7

Đăng ký nhận thông tin qua email để nhận được hàng triệu ưu đãi từ Muathuoctot.com

Tạp chí sức khỏe làm đẹp, Kem chống nắng nào tốt nhất hiện nay Thuoc giam can an toan hiện nay, thuoc collagen, thuoc Dong trung ha thao , thuoc giam can LIC, thuoc shark cartilage thuoc collagen youtheory dau ca omega 3 tot nhat, dong trung ha thao aloha cua my, kem tri seo hieu qua, C ollagen shiseido enriched, và collagen shiseido dạng viên , Collagen de happy ngăn chặn quá trình lão hóa, mua hang tren thuoc virility pills vp-rx tri roi loan cuong duong, vitamin e 400, dieu tri bang thuoc fucoidan, kem chống nhăn vùng mắt, dịch vụ giao hang nhanh nội thành, crest 3d white, fine pure collagen, nên mua collagen shiseido ở đâu, làm sáng mắt, dịch vụ cho thue kho lẻ tại tphcm, thực phẩm tăng cường sinh lý nam, thuoc prenatal bổ sung dinh dưỡng, kem đánh răng crest 3d white, hỗ trợ điều trị tim mạch, thuốc trắng da hiệu quả giúp phục hồi da. thuốc mọc tóc biotin

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp

Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ

Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp

Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc

Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em

Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng

Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất

Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu

Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực

Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng

Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa

Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng

Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.

Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.