-

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà...

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà... -

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu -

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

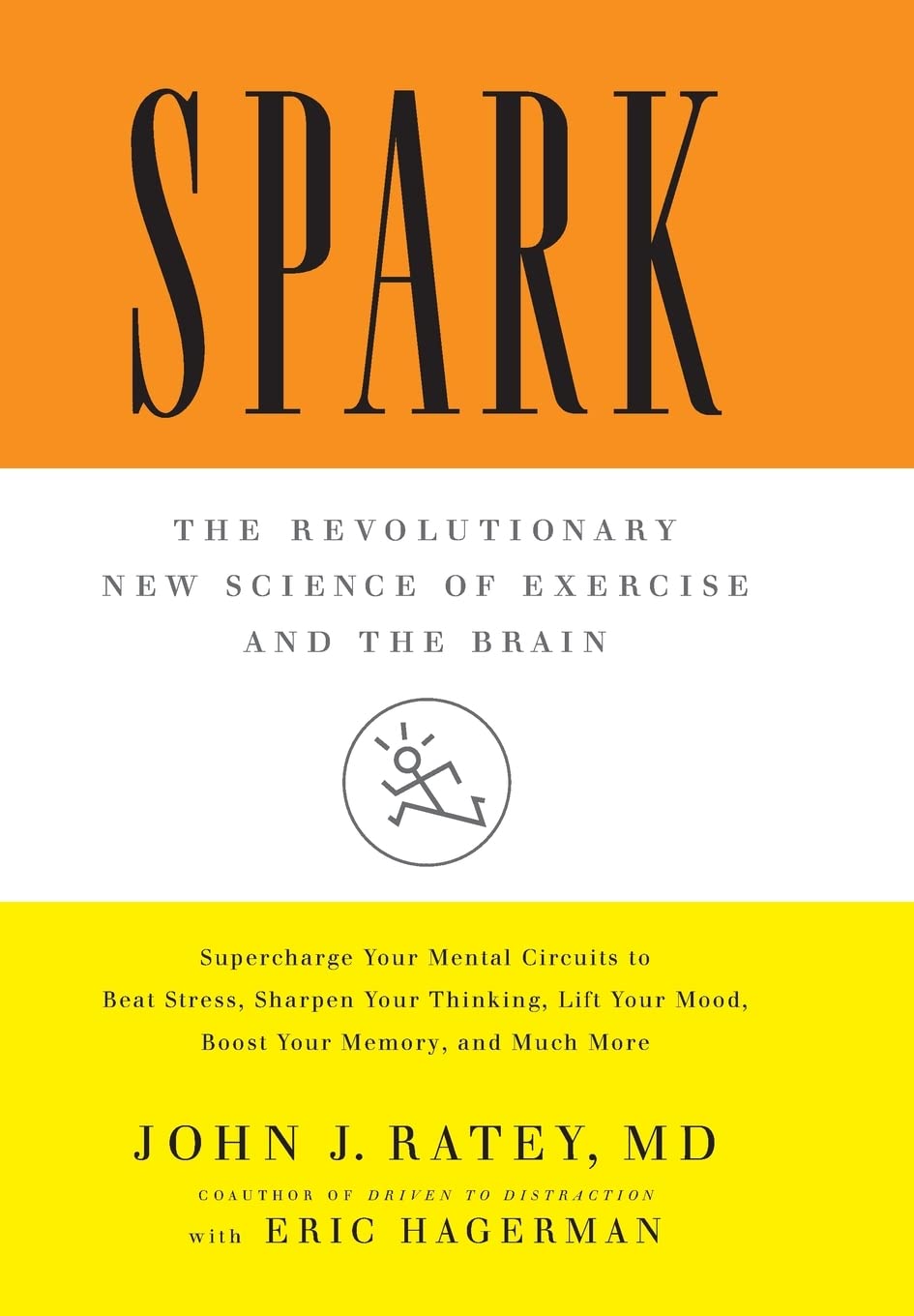

Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain

-

- Mã sản phẩm: 0316113506

- (2840 nhận xét)

- Publisher:Little, Brown Spark; 1st edition (January 10, 2008)

- Language:English

- Hardcover:294 pages

- ISBN-10:0316113506

- ISBN-13:978-0316113502

- Item Weight:1.14 pounds

- Dimensions:6.25 x 1 x 9.5 inches

- Best Sellers Rank:#50,663 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #14 in Aerobics (Books) #74 in Stretching Exercise & Fitness #262 in Cognitive Psychology (Books)

- Customer Reviews:4.6 out of 5 stars 2,840Reviews

Mô tả sản phẩm

Product Description

A groundbreaking and fascinating investigation into the transformative effects of exercise on the brain, from the bestselling author and renowned psychiatrist John J. Ratey, MD.

Did you know you can beat stress, lift your mood, fight memory loss, sharpen your intellect, and function better than ever simply by elevating your heart rate and breaking a sweat? The evidence is incontrovertible: Aerobic exercise physically remodels our brains for peak performance.

In Spark, John J. Ratey, M.D., embarks upon a fascinating and entertaining journey through the mind-body connection, presenting startling research to prove that exercise is truly our best defense against everything from depression to ADD to addiction to aggression to menopause to Alzheimer's.

Filled with amazing case studies (such as the revolutionary fitness program in Naperville, Illinois, which has put this school district of 19,000 kids first in the world of science test scores), Spark is the first book to explore comprehensively the connection between exercise and the brain. It will change forever the way you think about your morning run -- -or, for that matter, simply the way you think.

Review

"At last a book that explains to me why I feel so much better if I run in the morning! This very readable book describes the science behind the mind-body connection and adds to the evidence that exercise is the best way to stay healthy, alert, and happy!"―Dr. Susan M. Love, Dr. Susan Love's Menopause and Hormone Book and Dr. Susan Love's Breast Book

"Bravo! This is an extremely important book. What Cooper did decades ago for exercise and the heart, Ratey does in SPARK for exercise and the brain. Everyone--teachers, doctors, managers, policy-makers, individuals trying to lead the best kind of life--can benefit enormously from the utterly convincing and brilliantly documented thesis of this ground-breaking work. People know that exercise helps just about everything, except anorexia, but it will surprise most people just how dramatically it improves all areas of mental functioning. So, get moving! You're brain will thank you and repay you many times over."―Edward Hallowell, M.D., The Hallowell Centers

"This book is a real turning point that explains something I've been trying to figure out for years. Having experienced symptoms of both ADHD and mild depression, I have personally witnessed the powerful effects of exercise, and I've suspected that the health benefits go way beyond just fitness. Exercise is not simply necessary, as Dr. Ratey clearly shows, it's medicine."―Greg LeMond, Three-time winner of the Tour de France

"SPARK is just what we need-a thoughtful, interesting, scientific treatise on the powerful and positive impact of exercise on the brain. In mental health, exercise is a growth stock and Ratey is our best broker."―Ken Duckworth, M.D., Medical Director for the National Alliance on Mental Illness

About the Author

John Ratey, M.D., is a clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of numerous bestselling and groundbreaking books, including Spark, Driven to Distraction, and A User's Guide to the Brain. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Spark

By John J. Ratey Eric HagermanLittle, Brown and Company

Copyright © 2008John J. Ratey, MDAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-316-11350-2

Chapter One

Welcome to the RevolutionA Case Study on Exercise and the Brain

ON A SLIGHT swell of land west of Chicago stands a brick building, Naperville Central High School, which harbors in its basement a low-ceilinged, windowless room crowded with treadmills and stationary bikes. The old cafeteria-its capacity long dwarfed by enrollment numbers-now serves as the school's "cardio room." It is 7:10 a.m., and for the small band of newly minted freshmen lounging half asleep on the exercise equipment, that means it's time for gym.

A trim young physical education teacher named Neil Duncan lays out the morning's assignment: "OK, once you're done with your warm-up, we're going to head out to the track and run the mile," he says, presenting a black satchel full of chest straps and digital watches-heart rate monitors of the type used by avid athletes to gauge their physical exertion. "Every time you go around the track, hit the red button. What that's going to do-it's going to give you a split. It's going to tell you, this is how fast I did my first lap, second lap, third lap. On the fourth and final lap-which will be just as fast if you do it right-" he says, pausing to survey his sleepy charges, "you hit the blue button, OK? And that'll stop your watch. Your goal is-well, to try to run your fastest mile. Last but not least, your average heart rate should be above 185."

Filing past Mr. Duncan, the freshmen lumber upstairs, push through a set of heavy metal doors, and in scattered groups they hit the track under the mottled skies of a crisp October morning. Perfect conditions for a revolution.

This is not good old gym class. This is Zero Hour PE, the latest in a long line of educational experiments conducted by a group of maverick physical education teachers who have turned the nineteen thousand students in Naperville District 203 into the fittest in the nation-and also some of the smartest. (The name of the class refers to its scheduled time before first period.) The objective of Zero Hour is to determine whether working out before school gives these kids a boost in reading ability and in the rest of their subjects.

The notion that it might is supported by emerging research showing that physical activity sparks biological changes that encourage brain cells to bind to one another. For the brain to learn, these connections must be made; they reflect the brain's fundamental ability to adapt to challenges. The more neuroscientists discover about this process, the clearer it becomes that exercise provides an unparalleled stimulus, creating an environment in which the brain is ready, willing, and able to learn. Aerobic activity has a dramatic effect on adaptation, regulating systems that might be out of balance and optimizing those that are not-it's an indispensable tool for anyone who wants to reach his or her full potential.

Out at the track, the freckled and bespectacled Mr. Duncan supervises as his students run their laps.

"My watch isn't reading," says one of the boys as he jogs past.

"Red button," shouts Duncan. "Hit the red button! At the end, hit the blue button."

Two girls named Michelle and Krissy pass by, shuffling along side by side.

A kid with unlaced skateboarding shoes finishes his laps and turns in his watch. His time reads eight minutes, thirty seconds.

Next comes a husky boy in baggy shorts.

"Bring it on in, Doug," Duncan says. "What'd you get?"

"Nine minutes."

"Flat?"

"Yeah."

"Nice work."

When Michelle and Krissy finally saunter over, Duncan asks for their times, but Michelle's watch is still running. Apparently, she didn't hit the blue button. Krissy did, though, and their times are the same. She holds up her wrist for Duncan. "Ten twelve," he says, noting the time on his clipboard. What he doesn't say is "It looked like you two were really loafing around out there!"

The fact is, they weren't. When Duncan downloads Michelle's monitor, he'll find that her average heart rate during her ten-minute mile was 191, a serious workout for even a trained athlete. She gets an A for the day.

The kids in Zero Hour, hearty volunteers from a group of freshmen required to take a literacy class to bring their reading comprehension up to par, work out at a higher intensity than Central's other PE students. They're required to stay between 80 and 90 percent of their maximum heart rate. "What we're really doing is trying to get them prepared to learn, through rigorous exercise," says Duncan. "Basically, we're getting them to that state of heightened awareness and then sending them off to class."

How do they feel about being Mr. Duncan's guinea pigs? "I guess it's OK," says Michelle. "Besides getting up early and being all sweaty and gross, I'm more awake during the day. I mean, I was cranky all the time last year."

Beyond improving her mood, it will turn out, Michelle is also doing much better with her reading. And so are her Zero Hour classmates: at the end of the semester, they'll show a 17 percent improvement in reading and comprehension, compared with a 10.7 percent improvement among the other literacy students who opted to sleep in and take standard phys ed.

The administration is so impressed that it incorporates Zero Hour into the high school curriculum as a first-period literacy class called Learning Readiness PE. And the experiment continues. The literacy students are split into two classes: one second period, when they're still feeling the effects of the exercise, and one eighth period. As expected, the second- period literacy class performs best. The strategy spreads beyond freshmen who need to boost their reading scores, and guidance counselors begin suggesting that all students schedule their hardest subjects immediately after gym, to capitalize on the beneficial effects of exercise.

It's a truly revolutionary concept from which we can all learn.

FIRST-CLASS PERFORMANCE

Zero Hour grew out of Naperville District 203's unique approach to physical education, which has gained national attention and become the model for a type of gym class that I suspect would be unrecognizable to any adult reading this. No getting nailed in dodgeball, no flunking for not showering, no living in fear of being the last kid picked.

The essence of physical education in Naperville 203 is teaching fitness instead of sports. The underlying philosophy is that if physical education class can be used to instruct kids how to monitor and maintain their own health and fitness, then the lessons they learn will serve them for life. And probably a longer and happier life at that. What's being taught, really, is a lifestyle. The students are developing healthy habits, skills, and a sense of fun, along with a knowledge of how their bodies work. Naperville's gym teachers are opening up new vistas for their students by exposing them to such a wide range of activities that they can't help but find something they enjoy. They're getting kids hooked on moving instead of sitting in front of the television. This couldn't be more important, particularly since statistics show that children who exercise regularly are likely to do the same as adults.

But it's the impact of the fitness-based approach on the kids while they're still in school that initially grabbed my attention. The New PE curriculum has been in place for seventeen years now, and its effects have shown up in some unexpected places-namely, the classroom.

It's no coincidence that, academically, the district consistently ranks among the state's top ten, even though the amount of money it spends on each pupil-considered by educators to be a clear predictor of success-is notably lower than other top-tier Illinois public schools. Naperville 203 includes fourteen elementary schools, five junior highs, and two high schools. For the sake of comparison, let's look at Naperville Central High School, where Zero Hour began. Its per- pupil operating expense in 2005 was $8,939 versus $15,403 at Evanston's New Trier High School. New Trier kids scored on average two points higher on their ACT college entrance exams (26.8), but they fared worse than Central's kids on a composite of mandatory state tests, which are taken by every student, not just those applying to college. And Central's composite ACT score for the graduating class of 2005 was 24.8, well above the state average of 20.1.

Those exams aren't nearly as telling as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), a test designed to compare students' knowledge levels from different countries in two key subject areas. This is the exam cited by New York Times editorialist Thomas Friedman, author of The World Is Flat, when he laments that students in places like Singapore are "eating our lunch." The education gap between the United States and Asia is widening, Friedman points out. Whereas in some Asian countries nearly half of the students score in the top tier, only 7 percent of U.S. students hit that mark.

TIMSS has been administered every four years since 1995. The 1999 edition included 230,000 students from thirty-eight countries, 59,000 of whom were from the United States. While New Trier and eighteen other schools along Chicago's wealthy North Shore formed a consortium to take the TIMSS (thereby masking individual schools' performance), Naperville 203 signed up on its own to get an international benchmark of its students' performance. Some 97 percent of its eighth graders took the test-not merely the best and the brightest. How did they stack up? On the science section of the TIMSS, Naperville's students finished first, just ahead of Singapore, and then the North Shore consortium. Number one in the world. On the math section, Naperville scored sixth, behind only Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan.

As a whole, U.S. students ranked eighteenth in science and nineteenth in math, with districts from Jersey City and Miami scoring dead last in science and math, respectively. "We have huge discrepancies among our school districts in the United States," says Ina Mullis, who is a codirector of TIMSS. "It's a good thing that we've at least got some Napervilles-it shows that it can be done."

I won't go so far as to say that Naperville's kids are brilliant specifically because they participate in an unusual physical education program. There are many factors that inform academic achievement. To be sure, Naperville 203 is a demographically advantaged school district: 83 percent white, with only 2.6 percent in the low income range, compared with 40 percent in that range for Illinois as a whole. Its two high schools boast a 97 percent graduation rate. And the town's major employers are science-centric companies such as Argonne, Fermilab, and Lucent Technologies, which suggests that the parents of many Naperville kids are highly educated. The deck-in terms of both environment and genetics-is stacked in Naperville's favor.

On the other hand, when we look at Naperville, two factors really stand out: its unusual brand of physical education and its test scores. The correlation is simply too intriguing to dismiss, and I couldn't resist visiting Naperville to see for myself what was happening there. I've long been aware of the TIMSS test and how it points to the failings of public education in this country. Yet the Naperville 203 kids aced the test. Why? It's not as if Naperville is the only wealthy suburb in the country with intelligent, educated parents. And in poor districts where Naperville- style PE has taken root, such as Titusville, Pennsylvania (which I'll discuss later), test scores have improved measurably. My conviction, and my attraction to Naperville, is that its focus on fitness plays a pivotal role in its students' academic achievements.

THE NEW PE

The Naperville revolution started, as such things often do, with equal parts idealism and self-preservation. A visionary junior high physical education teacher named Phil Lawler got the movement off the ground after he came across a newspaper article in 1990 reporting that the health of U.S. children was declining.

"It said the reason they weren't healthy was that they weren't very active," recalls Lawler, a tall man in his fifties, with rimless glasses, who dresses in khakis and white sneakers. "These days everybody knows we have an obesity epidemic," he continues. "But pick up a paper seventeen years ago and that kind of article was unusual. We said, We have these kids every day; shouldn't we be able to affect their health? If this is our business, I thought, we're going bankrupt."

He already felt like his profession received no respect; schools had started cutting phys ed from the curriculum, and now this. A former college baseball pitcher who missed out on the majors, Lawler is a sincere salesman and a natural leader who became a gym teacher to stay close to sports. In addition to teaching PE at District 203's Madison Junior High, he coached Naperville Central's baseball team and served as the district coordinator for PE, but even in these respectable posts, sometimes he was embarrassed to admit what he did for a living. Part of what he saw in that article was an opportunity-a chance to make his job matter.

When Lawler and his staff at Madison took a close look at what was happening in gym, they saw a lot of inactivity. It's the nature of team sports: waiting for a turn at bat, waiting for the center's snap, waiting for the soccer ball to come your way. Most of the time, most of the players just stood around. So Lawler decided to shift the focus to cardiovascular fitness, and he instituted a radical new feature to the curriculum. Once a week in gym class, the kids would run the mile. Every single week! His decision met with groans from students, complaints from parents, and notes from doctors.

He was undeterred, yet he quickly recognized that the grading scale discouraged the slowest runners. To offer nonathletes a shot at good marks, the department bought a couple of Schwinn Airdyne bikes and allowed students to earn extra credit. They could come in on their own time and ride five miles to raise their grades. "So any kid who wanted to get an A could get an A if he worked for it," Lawler explains. "Somewhere in this process, we got into personal bests. Anytime you got a personal best, no matter what it was, you moved up a letter grade." And this led to the founding principle of the approach he dubbed the New PE: Students would be assessed on effort rather than skill. You didn't have to be a natural athlete to do well in gym.

But how does one judge the individual effort of forty kids at a time? Lawler found his answer at a physical education conference he organized every spring. He worked hard to turn the event into an exchange of fresh ideas and technologies, and to encourage attendance he talked the vendors into donating door prizes. Each year at the beginning of the conference, he would push a towel cart through the aisles, collecting bats and balls and other sporting goods. Cast in among the bounty one year was a newfangled heart rate monitor, which at the time was worth hundreds of dollars. He couldn't help himself; he stole it for the revolution. "I saw that son of a buck," he freely admits, "and I said, That's a door prize for Madison Junior High!"

During the weekly mile, he tested the device on a sixth-grade girl who was thin but not the least bit athletic. When Lawler downloaded her stats, he couldn't believe what he found. "Her average heart rate was 187!" he exclaims. As an eleven-year-old, her maximum heart rate would have been roughly 209, meaning she was plugging away pretty close to full tilt. "When she crossed the finish line, she went up to 207," Lawler continues. "Ding, ding, ding! I said, You gotta be kidding me! Normally, I would have gone to that girl and said, You need to get your ass in gear, little lady! It was really that moment that caused dramatic changes in our overall program. The heart rate monitors were a springboard for everything. I started thinking back to all the kids we must have turned off to exercise because we weren't able to give them credit. I didn't have an athlete in class who knew how to work as hard as that little girl."

He realized that being fast didn't necessarily have anything to do with being fit.

One of Lawler's favorite statistics is that less than 3 percent of adults over the age of twenty-four stay in shape through playing team sports, and this underscores the failings of traditional gym class. But he knew he couldn't have the students run the mile every day, so he set up a program of what they have termed " small-sided sports"-three-on-three basketball or four-on-four soccer-where the students are constantly moving. "We still play sports," Lawler says. "We just do them within a fitness model." Instead of being tested on such trivia as the dimensions of a regulation volleyball court, Naperville's gym students are graded on how much time they spend in their target heart rate zones during any given activity.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Sparkby John J. Ratey Eric Hagerman Copyright ©2008 by John J. Ratey, MD . Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

- Mua astaxanthin uống có tốt không? Mua ở đâu? 29/10/2018

- Saffron (nhụy hoa nghệ tây) uống như thế nào cho hợp lý? 29/09/2018

- Saffron (nghệ tây) làm đẹp như thế nào? 28/09/2018

- Giải đáp những thắc mắc về viên uống sinh lý Fuji Sumo 14/09/2018

- Công dụng tuyệt vời từ tinh chất tỏi với sức khỏe 12/09/2018

- Mua collagen 82X chính hãng ở đâu? 26/07/2018

- NueGlow mua ở đâu giá chính hãng bao nhiêu? 04/07/2018

- Fucoidan Chính hãng Nhật Bản giá bao nhiêu? 18/05/2018

- Top 5 loại thuốc trị sẹo tốt nhất, hiệu quả với cả sẹo lâu năm 20/03/2018

- Footer chi tiết bài viết 09/03/2018

- Mã vạch không thể phân biệt hàng chính hãng hay hàng giả 10/05/2023

- Thuốc trắng da Ivory Caps chính hãng giá bao nhiêu? Mua ở đâu? 08/12/2022

- Nên thoa kem trắng da body vào lúc nào để đạt hiệu quả cao? 07/12/2022

- Tiêm trắng da toàn thân giá bao nhiêu? Có an toàn không? 06/12/2022

- Top 3 kem dưỡng trắng da được ưa chuộng nhất hiện nay 05/12/2022

- Uống vitamin C có trắng da không? Nên uống như thế nào? 03/12/2022

- [email protected]

- Hotline: 0909977247

- Hotline: 0908897041

- 8h - 17h Từ Thứ 2 - Thứ 7

Đăng ký nhận thông tin qua email để nhận được hàng triệu ưu đãi từ Muathuoctot.com

Tạp chí sức khỏe làm đẹp, Kem chống nắng nào tốt nhất hiện nay Thuoc giam can an toan hiện nay, thuoc collagen, thuoc Dong trung ha thao , thuoc giam can LIC, thuoc shark cartilage thuoc collagen youtheory dau ca omega 3 tot nhat, dong trung ha thao aloha cua my, kem tri seo hieu qua, C ollagen shiseido enriched, và collagen shiseido dạng viên , Collagen de happy ngăn chặn quá trình lão hóa, mua hang tren thuoc virility pills vp-rx tri roi loan cuong duong, vitamin e 400, dieu tri bang thuoc fucoidan, kem chống nhăn vùng mắt, dịch vụ giao hang nhanh nội thành, crest 3d white, fine pure collagen, nên mua collagen shiseido ở đâu, làm sáng mắt, dịch vụ cho thue kho lẻ tại tphcm, thực phẩm tăng cường sinh lý nam, thuoc prenatal bổ sung dinh dưỡng, kem đánh răng crest 3d white, hỗ trợ điều trị tim mạch, thuốc trắng da hiệu quả giúp phục hồi da. thuốc mọc tóc biotin

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp

Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ

Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp

Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc

Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em

Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng

Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất

Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu

Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực

Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng

Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa

Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng

Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.

Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.