-

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà...

Thanh toán đa dạng, linh hoạtChuyển khoản ngân hàng, thanh toán tại nhà... -

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu

Miễn Phí vận chuyển 53 tỉnh thànhMiễn phí vận chuyển đối với đơn hàng trên 1 triệu -

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

Yên Tâm mua sắmHoàn tiền trong vòng 7 ngày...

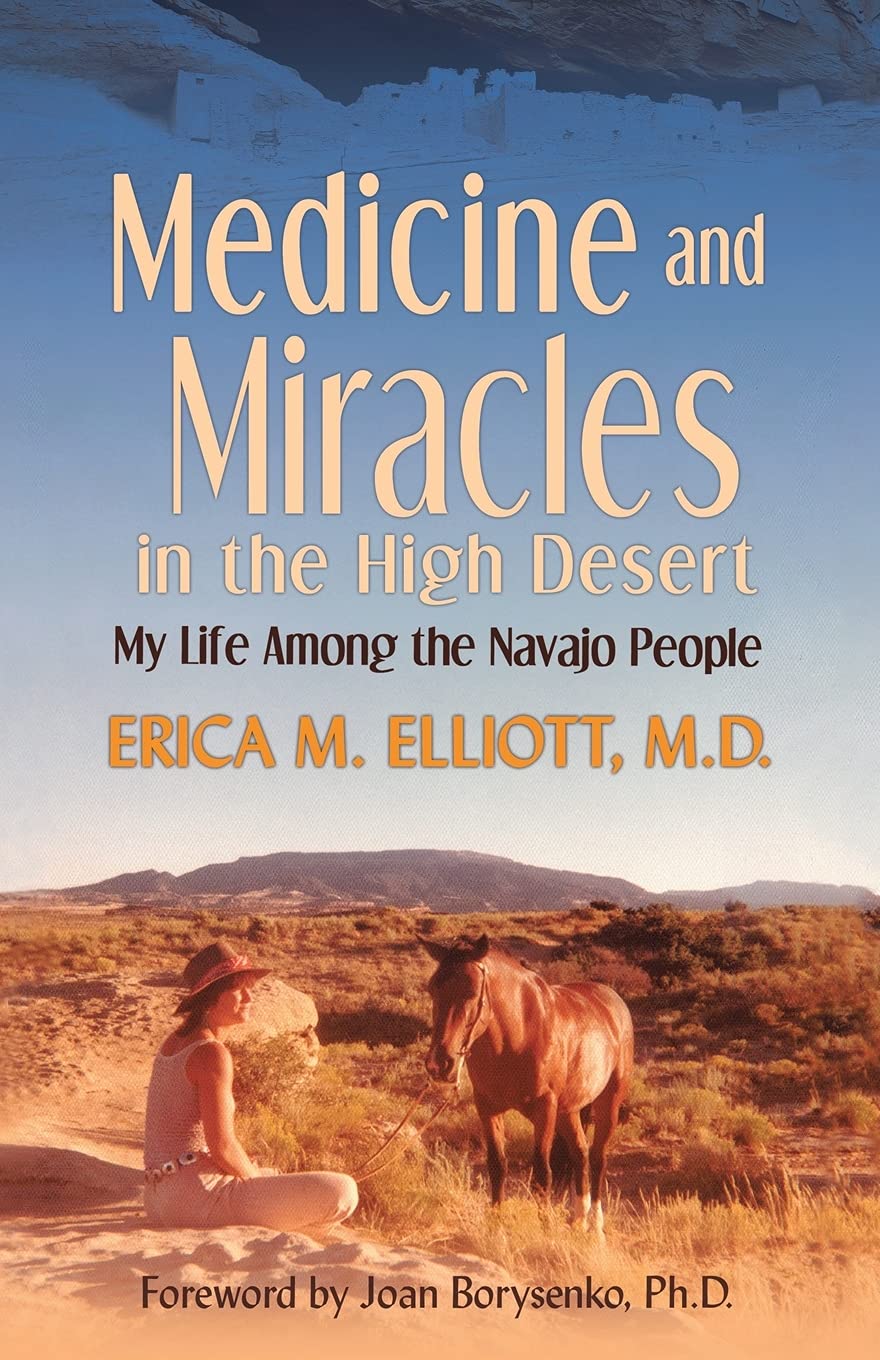

Medicine and Miracles in the High Desert: My Life Among the Navajo People

-

- Mã sản phẩm: 1982220988

- (248 nhận xét)

- Publisher:Balboa Press (February 18, 2019)

- Language:English

- Paperback:202 pages

- ISBN-10:1982220988

- ISBN-13:978-1982220983

- Item Weight:9.6 ounces

- Dimensions:5.5 x 0.51 x 8.5 inches

- Best Sellers Rank:#436,697 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #13,048 in Memoirs (Books)

- Customer Reviews:4.6 out of 5 stars 248Reviews

Mô tả sản phẩm

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Medicine and Miracles in the High Desert

My Life Among the Navajo People

By Erica M. ElliottBalboa Press

Copyright © 2019 Erica M. Elliott, M.D.All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-982220-98-3

Contents

Foreword, ix,Acknowledgments, xiii,

Introduction, xv,

1 | The Dead Medicine Man, 1,

2 | Chinle, Arizona, 11,

3 | Spirit Guide, 23,

4 | Medicine and Miracles in the High Desert, 29,

5 | A Walk Through Time, 41,

6 | Bilingual and Bicultural Education, 53,

7 | The Puberty Ceremony, 62,

8 | Terror off the Reservation, 67,

9 | My Friend Marshall, 79,

10 | Herding Sheep, 86,

11 | Butchering Sheep, 100,

12 | They Forget I'm White, 110,

13 | Walking in Another's Shoes, 118,

14 | Goodbye for Now, 128,

15 | The Peace Corps, 136,

16 | Back Home in the States, 150,

17 | Cuba, New Mexico, 154,

18 | State of Siege, 162,

19 | Road Man, 169,

Epilogue, 175,

Afterword, 181,

About the Author, 183,

CHAPTER 1

The Dead Medicine Man

* * *

Cuba, New Mexico, 1986

It was early summer — monsoon season — when I began my first job as a medical doctor, fresh out of training in family practice. An over- cast sky greeted me on the day of my arrival, along with thunder and lightning.

Overhead, a dark cloud released a curtain of rain that poured down hard against my car, driven by gusts of wind. Within minutes, the red clay road turned into slick mud. My two-wheel-drive Honda slid from one side of the road to another as I struggled up the long incline toward my new home in the foothills of the Jemez Mountains overlooking the little town of Cuba, located in a remote area of northern New Mexico.

A four-wheel-drive pickup truck sailed past me. The driver peered through the side window at me, no doubt wondering about the newcomer snaking around in the mud.

After I finally reached the two-room adobe house that I had rented sight unseen, I spent the next few hours hauling my belongings into the musty, mouse-infested building.

By the late afternoon, as the sun was low on the horizon, I decided to take a break and drive back down the road to town. I wanted to introduce myself to the doctor on duty and other staff members at the clinic.

I hopped back into my muddy car. The steep, slippery road meandered through spectacular scenery with otherworldly rock formations and towering ponderosa pine trees. The invigorating, crisp mountain air smelled delicious — even in the rain.

As the road rapidly descended, the landscape became more typical of the high desert — dotted with sagebrush and interspersed with piñon and juniper trees. Rabbits darted in and out of my peripheral vision as I concentrated on keeping my wheels outside the deeply carved ruts in the road.

Once I finally turned off the bumpy dirt road and reached the pavement, I spotted a series of long, low, ramshackle buildings made of partially rotted wood with tin roofs. The sign in front read "The Cuba Health Center." The building housed a nine-bed hospital along with a busy emergency room and outpatient clinic.

I tried to enter what looked like the front door but found it locked. I knocked on the door. No answer. I knocked louder and waited while the rain beat down on me. A Hispanic emergency medical technician in blue scrubs opened the door a crack, stuck his head out, and said, "What do you want?"

Taken aback, I responded warily, "I'm the new doctor." He looked me over briefly and then opened the door wide to let me in. He said, "We've been waiting for you." He had a mischievous smile on his face that I didn't know how to interpret.

The EMT led me to a small room where the medical practitioners wrote in their charts at the end of the day. Inside the room, the doctor on duty sat leaning back in his chair, with his feet on the desk. His piercing green eyes looked me over from head to toe in a friendly and flirtatious way. Then he took his feet off the desk, sat up in his chair, and said, "Hi, Erica. My name is Bill. You have no idea how glad we are to see you. I'm ready for a break from this place."

Bill had been trained in emergency medicine. The administration in Santa Fe hired him on a temporary basis to work at the clinic until a permanent doctor could be found — someone willing to serve time in this isolated stretch of the Southwest.

It was a few minutes past five o'clock. I asked Bill, "When do you get to go home and get some rest?"

His answer took me by surprise. "I'm going home right now. You're on call tonight. We'll be alternating nights on duty. It's just you and me, Doc. Tommy here will show you around," he said, gesturing to the EMT who had let me in. "He's one of our best EMTs. Good luck."

I could never have imagined what was waiting for me that night.

Before Tommy went off duty for the evening, he gave me a tour of the facility. We walked down the dark, poorly ventilated hallways, stopping intermittently for cursory introductions to the various staff members as they were leaving for the day. After the brief tour, Tommy turned to me and said matter-of-factly, "You'll be on night duty, starting now, until tomorrow morning. Then you'll be seeing patients in the clinic all day. Good luck."

I noted that both Tommy and Bill had ominously ended their sentences with "Good luck."

Tommy's casually dispensed news that my tour of duty was about to begin at that very moment made my mouth go dry and my heart race. Before my senses could register what was happening, the clinic began to pulse with action as patients came in after hours to be seen for their ailments.

On his way out the door, Tommy added that a Navajo medicine man had been run over repeatedly, with a vengeance, by a drunken acquaintance in a truck. The crime had happened in front of a bar about 30 miles away. The driver had been charged with attempted murder.

"Oh, I forgot to mention that the two EMTs we sent out to get him are stuck in the mud. One of them just radioed in and wants to know what he should do."

Not having a clue what the stuck EMTs should do, I asked Tommy how they would normally handle this situation. "Well, we would send out our other ambulance, but the battery is dead."

A third EMT managed to recharge the dead battery, then sped off into the last light of the sun. I bolted into the trauma room to make a quick study of where everything was located while I waited anxiously for their return. A kind nurse practitioner, fairly new to Cuba, stayed and helped me get set up.

As we were running back and forth from the supply room to the trauma room, I noticed something odd at the end of the long, unlit hall. Water was trickling in under the clinic's main entrance door. The stream of advancing water looked like a snake slithering sideways toward us, ever expanding in its width.

The nurse practitioner noticed the bewildered look on my face. "The maintenance man was supposed to fix that drainage problem today," she said, annoyed. "I guess he didn't get around to it. Whenever there's a big downpour lately, the water gets funneled right into the clinic." By the time she finished speaking, the water had reached my shoes and stopped just short of covering the tops.

The ambulance finally arrived back at the clinic. The EMTs carried the lifeless medicine man on a gurney into the tiny emergency room. He was not breathing and had no detectable blood pressure or pulse. He was DOA — dead on arrival.

Having only intubated anaesthetized dogs and plastic mannequins in my medical training, I took a few seconds to say a short, silent prayer, "God help me." I took a deep breath and charged forward.

Upon opening the patient's mouth to suction out the blood, I could see that the back of his throat was crushed. Intubation by the normal route would not be possible. I took another deep breath, grabbed a scalpel, and punctured a hole in the patient's neck below the thyroid gland in order to insert a breathing tube. As I pressed my finger on the incision to stop the bleeding, I yelled, "Where are the intubation tubes? Someone find me a tube." My voice rose in pitch. "I need it now." Someone let me know that the ER had recently run out of intubation supplies.

"Do you have a ballpoint pen?" I breathlessly addressed the EMT standing next to me. He nodded. "Give me your pen, but take the inside part out first. Hurry."

I pushed the empty barrel into the hole and blew into the makeshift tube. The ballpoint pen technique was something I had heard about from medics who had served in Vietnam. After I performed mouth-to-pen resuscitation for a few long minutes, the physician's assistant found an intubation tube in one of the drawers.

We replaced the ballpoint pen with the tube and then attached the oxygen supply. Those few minutes felt like an eternity.

The moment we completed the intubation, I allowed myself a nanosecond of amazement that I had just performed my first crycothyroidotomy on a real human being.

But the procedure did not do any good — given that the patient's heart had stopped beating before his body arrived at the clinic. One of the EMTs performed manual chest compressions with little success. It was time to try the defibrillator, electric paddles on the chest, to jolt the heart's electrical system into action.

With our feet in ever-rising water, it seemed like a good idea to move to another room to avoid electrocuting ourselves. We raced the gurney down the hall, looking for a room with a dry floor. We swung the gurney through the doorway into the supply room.

Although I had never used a defibrillator in my medical training, I knew where to place the paddles. I held my breath as I squeezed the paddles to activate them. The medicine man's body jumped and jerked on the gurney. After a couple of tries with the defibrillator, his heart began to beat erratically, without enough force to create a detectable blood pressure.

The EMT who drove the ambulance that had carried the medicine man back to the clinic did a chest x-ray with the patient supine on the gurney. The x-ray revealed that the medicine man's chest had been crushed, with all the ribs fractured, and blood had pooled in his lungs and chest cavity.

The medicine man needed to have a chest tube inserted to clear out the pooled blood. I wondered how doing the procedure on a human would compare with the ones we residents had been forced to perform on anaesthetized dogs during our medical training.

Most family practice residency programs do not train doctors for emergency room medicine. I had little choice but to do whatever I could to save this man's life, even though he was technically already dead.

I wondered if any of my classmates had experienced this level of trial by fire — unsupervised — on their first day of doctoring after graduation from residency training.

The nurse practitioner rummaged around and found the primitive, jerry-rigged glass jar with two tubes coming out of the stopper that the doctors at the Cuba Health Center used for draining blood and other secretions from the chest. With another wordless prayer, I pushed the scalpel into the precise spot between the ribs and inserted a tube that immediately reddened with escaping blood.

After one of the EMTs placed a catheter in the man's urethra to monitor urine output, there were no more procedures left for us to do. I could now stand back, breathe, and assess the situation.

The medicine man barely clung to life with a faint, erratic heartbeat. I was in way over my head and needed help. I had instantaneously gone from being a doctor-in-training to being a real doctor in the trenches, improvising on my own and using procedures that I had only read about in books or tried on plastic mannequins and helpless dogs. Fortunately, I had the support of experienced EMTs and nurses during that unforgettable evening.

At my request, one of the EMTs placed a call to the emergency department at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and relayed the dire situation to the doctor on duty. The ER doc immediately dispatched a trauma surgeon and crew by helicopter. Their estimated time of arrival: one hour.

By the time the helicopter landed, our resuscitation efforts had already ended after two hours of futile attempts. The EMTs notified the medicine man's family members of his death. Word spread rapidly throughout the community. His people had already started arriving at the clinic and were gathering in the waiting room even before we had pronounced the patient dead.

The trauma surgeon jumped out of the helicopter just as it landed on the little pad behind the clinic. He dashed toward the clinic ready to spring into action. I hung my head and said that the patient was dead, and related the whole story to the eager and highly caffeinated young doctor while I choked back my tears.

He put his hand on my shoulder and congratulated me for being able to get even a few heartbeats. He tried to comfort me by saying that only one percent of victims found "in the field" with a non-detectable blood pressure can be resuscitated. He took a brief look at the dead man with tubes in every orifice and then shook my hand and said with a sincere look on his face, "Good job. Keep up the good work."

He dashed back to the helicopter and took off. I darted into the bathroom and cried into a towel, muffling the sound of the sobs. I felt bowled over by all the tumultuous feelings that I had suppressed throughout the evening. After a few minutes, I reined in my emotions, rinsed my face with cold water and snapped back into action. The night was still young.

On my way to the waiting room to talk with the grieving family, one of the EMTs announced, "There's a pregnant Navajo woman with seizures on her way to the clinic."

In the meantime, all the chairs and standing areas in the waiting room had been filled with friends and relatives of the medicine man. At first, the Navajo people appeared angry that the medicine man had not been saved, probably without realizing the condition he had been in when the EMTs transported him to our little hospital. I assured them that we had done everything possible to save his shattered body. I handed one of the relatives a paper bag with the medicine man's turquoise necklace, silver bracelet, old turquoise earrings, and his headband, along with a few dollar bills that I'd found in his pockets.

I spoke from the heart, barely holding back the tears, in a combination of English and Navajo. Hearing the new doctor speak Navajo disarmed them. Their hostility dissipated before my eyes. Some even smiled with surprise. I expressed to them my heartfelt sorrow. When the Navajo people had no more questions for me to answer, I shook each person's hand as they filed past me. To the Navajos remaining in the room, I excused myself.

By then it was well past midnight. The next couple of hours I spent monitoring the pregnant Navajo woman, who was in the throes of potentially life-threatening seizures that were related to extremely high blood pressure — known as eclampsia. Her body convulsed repeatedly while her eyes rolled back in her head. I placed an IV in her arm and added magnesium sulfate to the intravenous solution, a mineral that is vital for stopping seizures. Magnesium relaxes the smooth muscles that line the blood vessels.

I sat with the stoic young woman, still dressed in her traditional clothing, until her blood pressure stabilized and the seizures stopped. An EMT wheeled her into the little nine-bed hospital, extending like a warehouse off the clinic, where the nurse on duty could monitor her.

A steady trickle of people came in throughout the night with problems less likely to raise my adrenaline levels, like sick babies with ear infections, a woman in false labor, a man with acute alcohol intoxication, and other more routine ailments. I felt relief wash over me because finally I could treat problems that I had been well trained to deal with.

When the Health Center finally quieted down that night, I decided to drive home to try to get a couple of hours of sleep.

But before I could get to the end of the hall, a young Hispanic woman came in moaning in labor. Her two sisters, mother, and grandmother accompanied her. I turned around and headed for the delivery room. The woman had received no prenatal care, which is not uncommon in isolated, rural areas.

The woman groaned and screamed from the pain, unlike Navajo women, who often labor silently. Her relatives gathered around her, holding her hand, stroking her head, and wiping her face with a cool washcloth.

Fortunately, the delivery went smoothly. As the family squealed with delight when the baby came out of the birth canal, I wiped away tears of joy with the back of my gloved hand. My first night shift as a neophyte doctor ended on a celebratory note.

The joy dissipated when I looked up at the clock and saw that it was already daytime. More patients would be streaming into the clinic in less than an hour. I had no time to go home and rest. No time even to shower or eat a real breakfast.

I walked out of the clinic into the sunlit morning after what had seemed like an interminable night shift taking care of a steady stream of emergencies. The rain had finally stopped. The air smelled clean and invigorating. I headed straight to the convenience store across the street and drugged myself with a sugary donut and washed it down with coffee so I could keep going after working all night.

A tall Navajo man walked over to the little table in the corner where I sat alone, eating my junk food breakfast. He said he wanted to talk to me. I recognized him; he had been in the room with the family members of the deceased medicine man. I braced myself for a barrage of criticism for not having saved his relative's life. Instead, he was polite and friendly. He asked me how I knew how to speak Navajo. I told him that long ago, when I was very young, I had been a schoolteacher on the reservation at Canyon de Chelly.

(Continues...)Excerpted from Medicine and Miracles in the High Desert by Erica M. Elliott. Copyright © 2019 Erica M. Elliott, M.D.. Excerpted by permission of Balboa Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Product Description

After her first week teaching at a boarding school on the Navajo Reservation near Canyon de Chelly, young Erica Elliott almost leaves in despair, unable to communicate with the children or understand cultural cues. But once she starts learning the Navajo language, the people begin to trust her, taking her into their homes and ceremonies. As she is drawn deeper into Navajo life, Erica has a series of profound experiences with the people, animals, and spirits of Canyon de Chelly. Fulfilling a Navajo grandmother’s prophecy, she returns years later as a medical doctor to offer her services to Navajo patients.

Endorsements

“Dr. Erica Elliott’s account of her life among the Navajo people is a story of high adventure that surpasses the wildest fiction. Elliott’s willingness to transcend her cultural conditioning and enter another complex society is an act of great courage, and reveals her boundless empathy and compassion. This book is sorely needed at this moment in America, when divisive voices incessantly warn us of the other, the foreigner, those who ‘are not like us.’ Mystery and Medicine in the High Desert: My Life Among the Navajo People reveals how diversity, inclusiveness, and tolerance can enrich our own society, which is a lesson on which our future may depend”

-Larry Dossey, MD, author of One Mind: How Our Individual Mind Is Part of a Greater Consciousness and Why It Matters.

“What a wonderful book! Elliott’s voice mesmerized me. For weeks after, I thought about her time with the Navajos. Such an inspiring, life-affirming, yet tough tale, woven through with a strong drive to realize one’s life path. Beautifully written. Elliott is an exciting new voice”

-Natalie Goldberg, author of Writing Down the Bones and Let the Whole Thundering World Come Home.

“Erica Elliott writes fearlessly with an original voice that grabbed me from the first page. Her true adventures on the Navajo Nation as a teacher, a shepherd, an emergency room doctor, and best of all, an open-hearted student immersed in a spiritually rich culture, make a great story. She leaves the reader with something to ponder: The abiding importance of reaching out to others with joy and respect. I love this book”

-Anne Hillerman, NY Times bestselling author of the Leaphorn/Chee/Manuelito mystery series.

“This is a powerful and personal book that is about courage and compassion. Reading it, one is drawn into the web of Dr. Elliott’s extraordinary life of service and learning with the Navajo of the American Southwest. We are fortunate to be able to accompany her on her remarkable journey”

-Rev. Joan Jiko Halifax, Abbot, Upaya Zen Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico, www.upaya.org.

About the Author

Erica Elliott is a medical doctor with a busy private practice in Santa Fe, New Mexico. A true adventurer, she has lived and worked around the world. She served as a teacher for Indigenous children on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona and in the mountains of Ecuador. She taught rock climbing and mountaineering for Outward Bound and led an all-women’s expedition to the top of Denali in Alaska. In 1993, Erica helped found The Commons, a cohousing community in Santa Fe. She raised her son Barrett in this safe and happy environment. Known as the “Health Detective,” she treats mysterious and difficult-to-diagnose illnesses at her clinic within The Commons. Erica is also a public speaker and has given workshops at various venues, including Esalen and Omega Institute. She is co-author of Prescriptions for a Healthy House. She blogs about medical insights and stories from her life at www.musingsmemoirandmedicine.com.

- Mua astaxanthin uống có tốt không? Mua ở đâu? 29/10/2018

- Saffron (nhụy hoa nghệ tây) uống như thế nào cho hợp lý? 29/09/2018

- Saffron (nghệ tây) làm đẹp như thế nào? 28/09/2018

- Giải đáp những thắc mắc về viên uống sinh lý Fuji Sumo 14/09/2018

- Công dụng tuyệt vời từ tinh chất tỏi với sức khỏe 12/09/2018

- Mua collagen 82X chính hãng ở đâu? 26/07/2018

- NueGlow mua ở đâu giá chính hãng bao nhiêu? 04/07/2018

- Fucoidan Chính hãng Nhật Bản giá bao nhiêu? 18/05/2018

- Top 5 loại thuốc trị sẹo tốt nhất, hiệu quả với cả sẹo lâu năm 20/03/2018

- Footer chi tiết bài viết 09/03/2018

- Mã vạch không thể phân biệt hàng chính hãng hay hàng giả 10/05/2023

- Thuốc trắng da Ivory Caps chính hãng giá bao nhiêu? Mua ở đâu? 08/12/2022

- Nên thoa kem trắng da body vào lúc nào để đạt hiệu quả cao? 07/12/2022

- Tiêm trắng da toàn thân giá bao nhiêu? Có an toàn không? 06/12/2022

- Top 3 kem dưỡng trắng da được ưa chuộng nhất hiện nay 05/12/2022

- Uống vitamin C có trắng da không? Nên uống như thế nào? 03/12/2022

- [email protected]

- Hotline: 0909977247

- Hotline: 0908897041

- 8h - 17h Từ Thứ 2 - Thứ 7

Đăng ký nhận thông tin qua email để nhận được hàng triệu ưu đãi từ Muathuoctot.com

Tạp chí sức khỏe làm đẹp, Kem chống nắng nào tốt nhất hiện nay Thuoc giam can an toan hiện nay, thuoc collagen, thuoc Dong trung ha thao , thuoc giam can LIC, thuoc shark cartilage thuoc collagen youtheory dau ca omega 3 tot nhat, dong trung ha thao aloha cua my, kem tri seo hieu qua, C ollagen shiseido enriched, và collagen shiseido dạng viên , Collagen de happy ngăn chặn quá trình lão hóa, mua hang tren thuoc virility pills vp-rx tri roi loan cuong duong, vitamin e 400, dieu tri bang thuoc fucoidan, kem chống nhăn vùng mắt, dịch vụ giao hang nhanh nội thành, crest 3d white, fine pure collagen, nên mua collagen shiseido ở đâu, làm sáng mắt, dịch vụ cho thue kho lẻ tại tphcm, thực phẩm tăng cường sinh lý nam, thuoc prenatal bổ sung dinh dưỡng, kem đánh răng crest 3d white, hỗ trợ điều trị tim mạch, thuốc trắng da hiệu quả giúp phục hồi da. thuốc mọc tóc biotin

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN

KHUYẾN MÃI LỚN Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp

Hỗ Trợ Xương Khớp Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ

Bổ Não & Tăng cường Trí Nhớ Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp

Bổ Sung Collagen & Làm Đẹp Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc

Bổ Thận, Mát Gan & Giải Độc Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nam Giới Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới

Chăm Sóc Sức khỏe Nữ Giới Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em

Chăm sóc Sức khỏe Trẻ Em Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng

Thực Phẩm Giảm Cân, Ăn Kiêng Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất

Bổ Sung Vitamin & Khoáng Chất Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu

Bổ Tim Mạch, Huyết Áp & Mỡ Máu Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực

Bổ Mắt & Tăng cường Thị lực Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng

Điều Trị Tai Mũi Họng Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa

Sức Khỏe Hệ Tiêu hóa Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng

Chăm Sóc Răng Miệng Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.

Chống Oxy Hóa & Tảo Biển.